Story: Kittin Likitparinya

Thai society has begun to anticipate and prepare for its transition into a super-aged society. The healthcare and human resource management sectors of the government are in the process of implementing new measures in response to demographic changes. However, our entry into a super-aged society will bring sweeping changes to

Funeral customs and traditions have always changed throughout different periods of history. Once upon a time, Thai people did not mourn in black, but dressed in white, dark purple, or dark blue, according to the individual’s age relative to the age of the deceased. Nowadays, Thais customarily mourn in black, regardless of age. Likewise, the traditional Chinese Gong De (funeral memorial) never included, in any shape or form, the burning of paper palaces and cars to accompany the deceased into the afterlife.

Changes to tradition were possible before, and are therefore possible now, especially if they are made in accordance with the last wishes of the deceased. In addition to providing a sense of closure to the deceased and their close relatives, these changes are, in a way, the last message the deceased leaves in this world, and must be respected as such.

Are funerals arranged in accordance with the wishes of the deceased in Thailand?

At the beginning of April, 2019, a funeral took place at twilight in Sala 12 at Wat Bungthonglang that, to the casual onlooker, would have seemed no different from a typical funeral. Upon closer look, however, it would become apparent that those gathered were not dressed in customary black attire. Furthermore, the host received a book in place of the conventional envelope of money, and a song called ‘Ning Nong’ by Sangthong Seesai (a famous Northeastern song), prefaced the beginning of the funeral prayers within the sala.

Ms. Chontharn Tancharakorn later explains that funeral proceedings were all in accordance with the final wishes of her father, Mr. Parin Tancharakorn, and had been discussed beforehand in the last few months of his life.

• I ask for five days of funeral prayers, each for a member of my family, and to choose the temple where my funeral rites will be held, as well as where my bones will be buried • I ask that ‘Ning Nong’ by Sangthong Seesai be played at my funeral and also that there be no mourning, for death is not defined by suffering. Therefore, come to the funeral dressed in any color you wish, but do not wear black. • I’d like postcards of the sea, the embodiment of freedom, on them to be distributed as funeral gifts. Printed on the picture will be a line from the song “Something good” by the Nanglen band, which I have often repeat to my family, “Not every day may be a good day, but there is always something good in every day.” • In addition to the postcards, I would like one of my favorite books, Ajarn Pramuan Pengchan’s “The Last Light”, to be given out at the funeral. •

How Mr. Tancharakorn Came to Plan His Own Funeral

Mr. Tancharakorn’s funeral was held in early May, 2019. Four months earlier, on the first of January, the Tancharakorn family learned that Mr. Tancharakorn had metastatic cancer. They had less than four months to prepare for his passing.

Although Mr. Tancharakorn had once participated in Phra Paisal Visalo’s “Happy Death Day” workshop — in which participants are guided through a contemplation of their own death — and left with a “Healing Journal” in hand (the “Healing Journal” is a living will that states the writer’s preferences for end-of-life treatment or care should they be unable to communicate them directly). However, the book was nowhere to be found after he received his diagnosis.

This meant that the family had to begin the process again.

“My father’s cancer was at an advanced stage. Since we were unable to find his Healing Journal, I decided that I had to find a way to talk about the end with my dad,” Ms. Chontharn says. Frank conversations about death are generally considered inauspicious among Thai-Chinese families and stay unmentioned, locked away in everyone’s hearts. Mr. Tancharakorn was no different. However, his family was able to get him to lay down these superstitions, and talk about what he wanted at the end of his life.

“Actually, we had already begun talking about it when my father was in the hospital, because we didn’t know how much time he had left. At the time, my father still held on to the old-fashioned Chinese belief that to talk about one’s death was akin to an open invitation to the reaper.

“But we talked about it in a lighthearted manner, at times joking, at times serious. My father relaxed once we began talking about his death, and sometimes bantered along with us, such as asking for the song, ‘Ning Nong’, to be played at the ceremony.

“Once my father became more comfortable, I began to throw out more difficult questions, such as asking him about the finer details of the funeral. I asked him about the traditional mourning period, to which he responded that he didn’t want one, because he did not think of death as suffering. Then I asked him about the length of the funeral prayers… all the way up to the cremation ceremony, when he said that he wanted his favorite book by Ajarn Pramuan Pengchan to be the funeral gift.”

“We began talking about it sometimes lightheartedly, sometimes seriously, but both of us always knew in the moment that it was a serious conversation,” says Ms. Chontharn.

Mr.Tancharakorn and his family were able to have an open conversation about what he wanted for his funeral because his children plucked up the courage to ask him what he truly desired. The conversation moved at his pace and comfort, with everyone paying attention to and centering his feelings and needs. In this way, they were able to relieve his anxieties over the discussion of death, and talk openly and honestly with one another.

The Value of Planning One’s Own Funeral

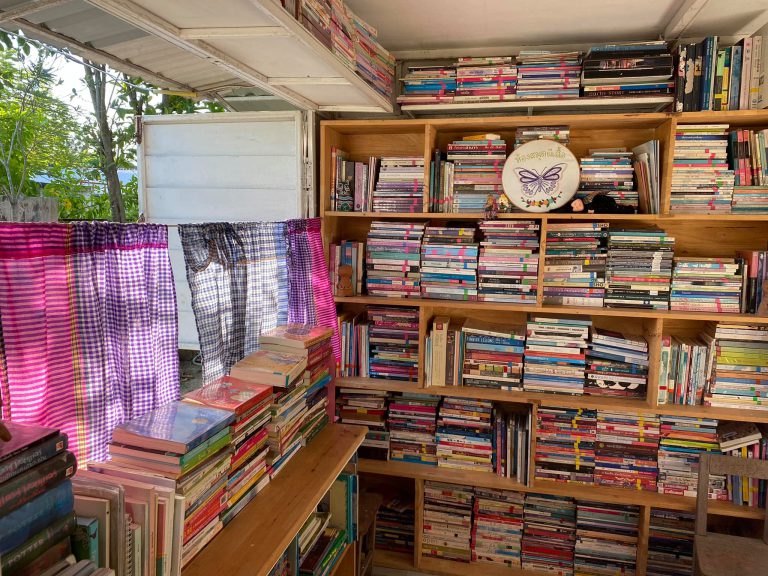

Mr.Tancharakorn’s funeral deviated from tradition, but not to anyone’s loss and, as a matter of fact, to many advantages. For one, his children and close relatives came together to organise the funeral without any conflict, because Mr. Tancharakorn‘s instructions took precedence, and to be able to fulfil his last wishes brought them closure. Furthermore, all the books (totalling 1973 titles) that the guests were asked to bring as gifts in place of cash envelopes were ultimately donated to the Chaiyaphum Monastery and Kindergarten, and made merit for the deceased, his living relatives and all the funeral guests.

Planning one’s own funeral is another course of action available to those who are preparing for their own death. Though these funerals sometimes diverge from tradition, they have many potential advantages and no drawbacks to speak of.

*Note: Mr. Parin Tancharakorn’s funeral was organised by the Tancharakorn family and held at Sala 12, Wat Buangthonglang on 18-22 April, 2019. The writer would like to thank Ms. Chontharn Tancharakorn and her family for their contribution to the article.