Story: Patwajee Srisuwan

Why should cancer patients join a cancer support group? Won’t being surrounded by other sick people make them feel worse?

This article will provide an answer to these questions through the lens of Orathai Chafu or “Jim’s” experiences. Her first encounter with cancer was through a lung cancer diagnosis in her late twenties. Once her symptoms had abated with treatment, she began helping chronically-ill and cancer patients at hospitals or in her personal network in person, before becoming the leader of a cancer support group in the present.

Jim’s lived experiences as a cancer patient, caregiver and cancer support group leader all attest to the fact that when well-run, a cancer support group is a “space for letting go” and “a life-giving space”. While the role of medical science is the treatment of the physical body, the support group is an impressive healer of the spirits of patients and their families. That is because the support group is a space of mutual understanding between “companions in suffering” and “those in the same boat”.

This article will recount Orathai’s experiences and insights into what the qualities of a cancer support group committed to the healing of patients and their families are.

Support Groups… Are Good For Patients and Their Families

No small number of cancer patients choose to keep their suffering and anxiety over their condition to themselves because they are afraid of the effects expressing them will have on the people close to them. The more they try to hide it, the more tortured they become. Their unspoken suffering turns into irritability or depression. Full of concern and with good intentions, relatives and caregivers, on the other hand, also become stressed out when the patient does not cooperate with them in the way that they want.

Joining a cancer support group opens up space for patients and caregivers to get what they have been repressing off their chest. One patient’s or caregiver’s story may be similar to others’. When a patient shares how they have been feeling and talks about their relationships to their caregivers, a caregiver in the circle may receive new insight into how their patient may be feeling. The support group is a wonderful space for learning from and understanding the other party’s perspective.

“People who have gone through the same experiences tend to connect with each other quickly. A patient once told me that the voice of another cancer patient sounded like a version of their own, and that patient’s caregivers were just like their own caregivers as well — constantly telling them to eat, eat, eat. Seeing yourself in someone else is powerful. In the group, wherever something touches everyone, they’ll respond “yes, yes” at the same time, and reflect on how they now understand how the other party was feeling,” says Orathai.

“Relatives or caregivers share the root of their suffering, which is when the patient does not cooperate with them in the way that they expected. Some relatives don’t understand it, they say ‘I’ve been doing and trying my best; why do they speak to me in that way, why won’t they eat the food that I’ve prepared for them’. Or, ‘when they’re with other people they behave so nicely, they appear so strong, once they’re with me they’re acting weak — why won’t they fight, why won’t they appear strong for me?’ Once relatives and caregivers hear other patients talk about how they feel towards their own caregivers, they are given insight into the perspective and inner world of patients. They realize that their concern can contribute to a patient’s suffering when, for example, forcing a patient to eat because they think the patient is hungry — that the patient won’t build up their strength if they don’t eat — when actually, the patient may be hungry but is unable to eat because their body can’t hold down food.”

The benefits or consequences of attending a support group will not be the same for each person, as everyone has different needs and lived histories. Some participants find the answers to certain questions, others may leave a meeting having decided upon a course of treatment. However, what every single person receives is the life-giving energy that derives from being understood and accepting one’s suffering through talking and extending love to one another.

The Secrets to a Successful Support Group

Facilitating a group so that everyone is comfortable and benefits from the session according to their goals isn’t easy. This is especially true with a cancer support group for patients and caregivers, a group of people with particular physical and emotional fragility. Orathai explains that she “has to mobilize her knowledge, creativity and experience” throughout over a decade’s work with cancer patients and caregivers. Below is her summary of the secrets, or the key factors to her success, as a support group leader:

- Faith. Have faith that each person has the ability to find a way out of their difficulties in life. However, they may have walls or shadows within that prevent them from seeing it. We have to trust that everyone already holds the key in their hand. Otherwise, we will try to find answers or a verdict for them, or sway others into adopting our own beliefs.

- Perceptiveness. Recognize when someone is trying to exert influence over the group, taking up space or censuring other people. Some newcomers may want to convince everyone to their point of view. We must keep saying that our experiences are only one set of experiences, we can not use them to measure the others’ success. After someone shares a personal story, we should remind the group that this is but one experience. When we find creative ways to say it, the group becomes a lot more conscious.

- There are no protagonists on this stage. To open the discussion, we should remind everyone that they are all important, and that every single person in the room is both a teacher and student. If we position ourselves as the protagonist, then everyone will be focused on us. We have to hold space for everyone. Encourage and inspire confidence in anyone who has yet to talk, or is too shy to speak up. Everyone should be seated in a circle. It is dangerous to stage ourselves in front of them and talk, because we become the center of attention. The support group should be a space for everyone to truly learn from one another. It is not a space where people come to imitate us, or to try and recover like us.

- Sensitivity to context. Context and time will shape the organisation of a support group for patients and caregivers. Sometimes, patients and caregivers have to be seperated because there are certain topics, such as private suffering or tensions, that each party can not share in the others’ presence. In other situations, we can mediate a conversation between patients and caregivers. When there is ample time, the two groups can be facilitated separately. There is no perfect formula. What is important to note is that large groups will naturally fragment into smaller ones. For example, the liver cancer patients, or patients with similar symptoms, may get into a group and share their experiences among themselves. This should be taken as a consequence of composition of the participants.

- Lead wholeheartedly. The people who attend the support group must be fully committed. Some show up because their doctor or family told them to. During the session, they may act hostile or apathetic, checking the time often or attempting to distract others. As the group leader, we must use our experience and creativity to manage the situation. Sometimes if people are chatting, I can choose to playfully or firmly say “we will only speak when others are ready to listen”, and everyone usually quiets down and refocuses.

- Include Activities that Engage Direct Experience. Most organisations host support groups that last half a day and are predominantly conversation-based. However, if the sessions were lengthened into, say, a two day workshop, activities such as self-questioning exercises and wellness skills classes (such as yoga for patients), that directly engage participants’ lived experiences can be incorporated.

Examples of Cancer Support Groups

Orathai has been part of many cancer support groups. Below is a list of what she considers to be successful cancer support groups that are structured to engage and benefit their members, maintain continuity, and incorporate a thorough grounding in health and wellness.

- Happy Cancer is a group that is open to the public, the result of a cancer support group on social media that developed into a community that meets offline. Each meeting is attended by 12-20 patients and relatives. All participants register beforehand, and collectively determine when the meetings begin and end. Usually, meetings start at 10am and finish at around 3pm.

- Healing From Loss is a support group for nurses that are struggling as a consequence of working in healthcare, such as their encounters with death. The group has 7-8 members; it’s goal is the spiritual healing and nurturing of nurses who are suffering from the loss of loved ones or their patients.

- Healing with Faith and Love is a support group of chronically-ill patients and their relatives organised by The Chiang Rai Prachanukroth Hospital. There are around 20 group members who meet for half a day. The group has developed an extended 2 day workshop, which is at present on hiatus due to changes in hospital policy.

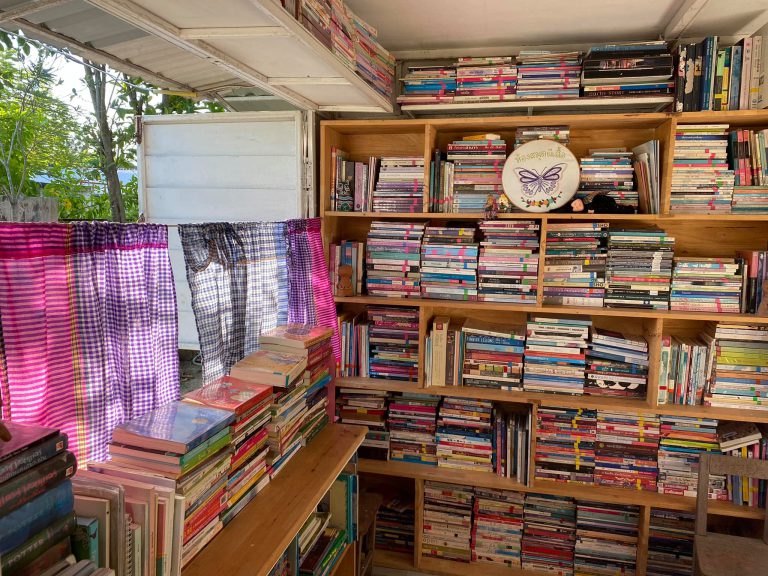

Photos: Orathai Chafu’s Facebook Page