Story: Woraphong Wechamaleenonda

“This is how the buddhist discipline cares for sick monks. Once ordained, monks renounce their families; only the preceptor’s acquaintances can care for his disciples when they are unwell. If the preceptor is unavailable, then other preceptors and monks in the community will take care of him. In the event that there is no one to care for him, the sick monk will have to make penance” — Phra Vichit Thammachito, founder of the Santibhavan, a nursing home for monks in Thailand.

Over the last decade, there has been a growing awareness of the importance of holistic, palliative care in Thai society, which has drawn monks into the role of emotional and spiritual counsel to buddhist patients. However, while palliative care systems for laypeople have come a long way, there is an absence of support structures for terminally-ill monks. Since hospitals are not prepared to take care of monks in a way that accommodates their religious discipline, while at the same time neither the temples or families themselves can give them proper end-of-life care, many monks are neglected in their last stage of life.

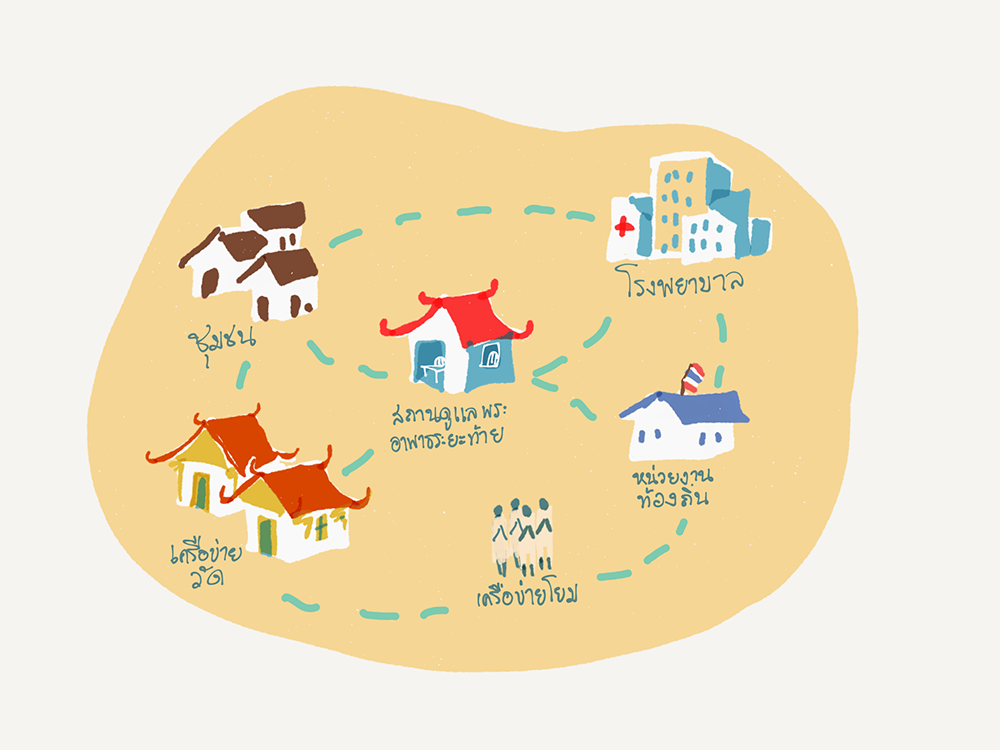

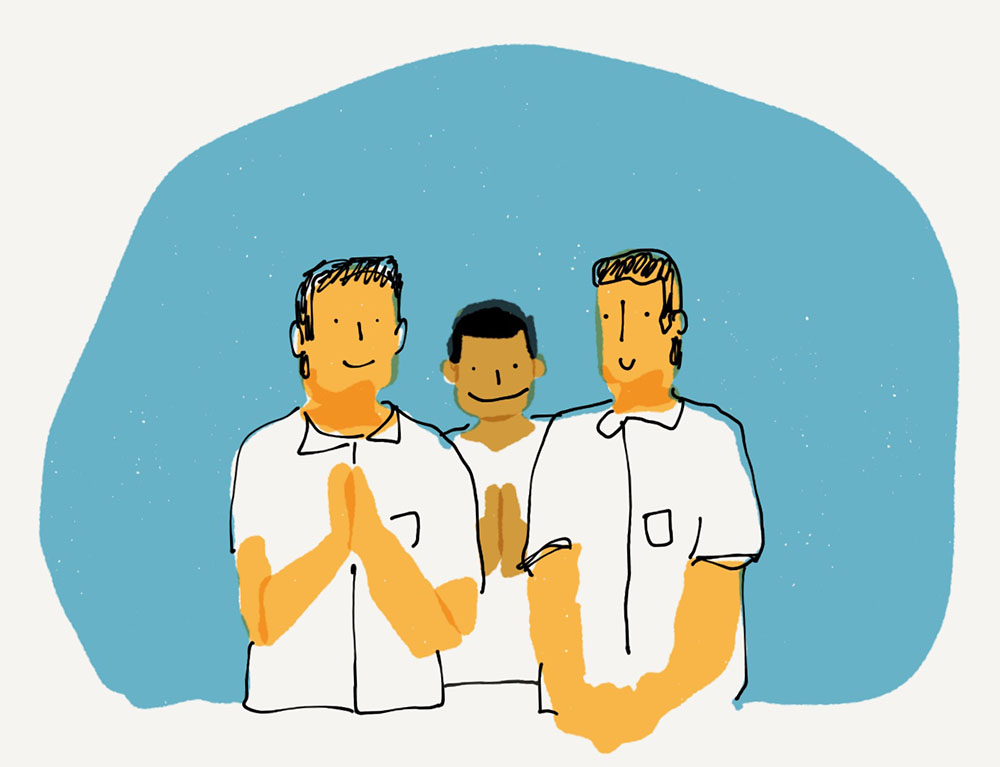

This reality inspired Phra Vichit Thammachito and his collaborators to create a hospice specifically for monks in their last stage of life (see “Santibhavan”: The Story Behind Thailand’s First Hospice for Monks). They hope to introduce a palliative care template that other monks from different areas can adapt into possible support systems for themselves and their acquaintances in the future. A small group of around fifteen monks, nuns and laypeople interested and experienced in medical care were invited to an event that outlined a palliative care framework for monks with Phra Paisal Visalo, the abbot of Wat Pa Sukato, and Mr. Pornsap Tesakulcharoen, head of the palliative care ward for monks at the Priest Hospital, where they shared their experiences and insights with each other to understand their respective challenges in providing proper care for sick monks and possible solutions that align with religious discipline. Most important was for participants to get to know one another, in order to collectively sustain the palliative care network for monks in the long-term.

Phra Paisal Visalo remarks that Thai people’s interest in dying well has grown steadily in the past fifteen years. Greater importance is given to preparing the body and the spirit early on: living in accordance with the buddhist principles, teaching the spirit to learn to let go, and practicing mindfulness of emotions that can disturb the spirit in life and in death. Environments, places and processes for taking care of the body and spirit in the final moments that will aid in a good death have also been introduced. In fact, in certain regions of the country such as the northeast, small organisations such as the Karunrak Centre at Srinagarind Hospital have been offering training courses in palliative care for healthcare professionals in every province and district in the northeast. Now, patients in practically every tambon (sub-district) have access to palliative care, and can choose to have a good death at home, though unfortunately, this growing interest has been confined to the secular areas of society for the most part, while there has been little activity in the religious sphere.

Phra Paisal recognizes that monks should prepare themselves in body and spirit for death as well, especially in regards to choosing where they want to die. There is no need for monks to pass away at hospitals as has been the case traditionally, without asking how they can be aided in dying well. Though the latter option is not an easy one to facilitate, for a limitation of the buddhist institution in the present day is that temples do not have the capacity to look after terminally-ill monks. One contributing factor is that the number of monks per temple is decreasing, but the significant cause is that monks are not taking care of one another. They tend to live independently, to each his own, and therefore, when they become terminally ill, they have no choice but to ask their relatives outside of the monkhood to take them in or to go to the hospital, as they have nowhere else to go. However, both these avenues often come into conflict with their religious practice.

Monks residing in temples must return to caring for their fellows in the monkhood from the beginning of sickness to their last moments. It would be even better if temples can provide end-of-life care, though there should still be options for monks who decide that they do not want their life prolonged through hospital treatment and are also unable to rely on the temple they live at. Therefore, the construction of hospices for monks is of great importance and, we believe, will receive support from many people as great strides have been made in palliative care in the secular sector, with networks for procuring equipment and medicine and enlisting no small number of volunteer, doctors and nurses that want to help terminally-ill patients who wish to die well at home.

It is imperative that monks join hands with other networks and create places where terminally-ill monks are aided in peaceful death in an environment, absent of life-prolonging technology, that serves the “Triratna” and the practice of meditation in times of sickness and pain, where death is taken as one’s teacher until one is ready to let go of everything. Then, we will see that a good death is possible for all.

Caring for Sick Monks at the Priest Hospital

The other speaker, Mr. Pornsap Tesakulcharoen, who began working at the Priest Hospital right after graduation and has been there for over thirty years, touched on different approaches to caring for sick monks and answered every one of the participants’ questions by first explaining that the Priest Hospital is a hospital under the Department of Medical Services with a 300 bed capacity that provides care for sick monks twenty four hours a day. It covers all departments found in a regular hospital, aside from a pediatric centre and an OBGYN department. In the event that a sick monk needs treatment that exceeds the capacity of the hospital, there is a system in place for sending them to affiliated hospitals. For example, if heart bypass surgery, which requires specialised tools, is needed, then the patient is sent for further treatment at Rajavithi Hospital.

The Priest Hospital takes in Thai monks from across the country and treats them without charge, regardless of the form of universal healthcare they have, because the hospital is able to sustain itself through buddhist donors rather than its government budget. The hospital therefore does not have to abide by a patient’s eligibility for state healthcare but can provide treatment to anyone as buddhists.

As for the monks themselves, most expect hospitals to be institutions with the best understanding of treating and looking after them. However, Mr. Pornsap acknowledges that hospitals still present obstalces, as aspects of the healthcare process are in contradiction with monastic discipline. This is in part because there aren’t enough male nurses, which makes caring for monks an inconvenience in many regards. Add to this the fact that different types of monks come to the hospital for treatment — some enter the monkhood to satisfy their basic needs or for benefits such as free healthcare. These monks forget that though a patient, they are still a monk, and thus behave inappropriately, which leads certain members of the hospital staff and their attendants to also forget that their patient is a monk. They may give orders to the monk as if he were a regular patient, and forget to consider what is appropriate according to buddhist practice.

This has been a problem for a long time, and no one knows this better than the director of the Priest Hospital. He therefore places particular emphasis on providing healthcare for monks that follows buddhist practice and encourages his staff to regard their patients as monks — that they are looking after monks, and not a regular patient in the guise of a monk. The buddhist precepts must be observed from the very moment the monk steps across the threshold of the hospital until his departure. Only then can their actions count as an act of merit for him.

Inadequate care for all aspects of monks’ well-being is another concern of the monks attending the seminar, who raise the question of why there aren’t any regional Priest Hospitals when there are monks living throughout the country. Mr. Pornsap responds that this is because the Ministry of Public Health already has a policy that requires that large hospitals have a designated building for monks. Additionally, a number of monks who recognize the importance of proper healthcare for monks have built many designated clinics at various hospitals across the country. The problem with most of the clinics that have been built is that, in practice, they are not actually used by monks, partly because few monks visit for healthcare services while other areas of the hospitals are overwhelmed with regular patients. As a result, hospitals admit male and female laypeople for treatment at the monks’ clinic and there ends up being too much intermixing.

To solve this problem, the Priest Hospital is in the process of introducing policy on visiting and evaluating monks’ clinics at various hospitals. Representatives will provide feedback and assist in improvements that will then qualify the hospital for certification in monks’ healthcare services that are in keeping with the conventions of monastic discipline. Monks of integrity, who uphold the monastic discipline, will feel grateful when they visit for treatment. Additionally, the initiative will also foster connection and collaboration between various monks’ clinics, which are all equipped with methods for properly caring monks. For example, once the Priest Hospital learned of the monks’ ward at Srinagarind Hospital, renown for treating forest monks, representatives from the Priest Hospital visited to observe the way they organised their space, their treatment methods and the behavior of the staff, and appropriate certain aspects to improve the quality of care at the Priest Hospital. They also made improvements to the Priest Hospital staff, such as by introducing a policy on only employing male nurses and increasing the staff’s salary and benefits to a more suitable amount.

End-of-life Care for Hospitalized Monks

Since the Priest Hospital operates under the Department of Medical Services, which has been appointed as the vanguard of Thai palliative care by the Ministry of Public Health, much importance is given to the care of terminally-ill monks, with designated hospital beds and a supervising committee since 2007.

One channel by which sick monks access palliative care is by already being admitted for treatment at the Priest Hospital, where doctors may surmise that he is in the last stage of his life. Or, they may have been receiving treatment at another hospital until entering the late stage of life and have nowhere to go, as neither the temple or their relatives is able to take them in and care for them due to an absence of caregivers or other complications. Therefore, they ultimately have to be sent to the Priest Hospital. Regardless of the form of palliative care that their patients need, the Priest Hospital is committed to taking care of them to the best of their ability, addressing all aspects of treatment in a holistic manner.

Mr. Pornsap observes that attending to the monks’ physical well-being isn’t difficult, but caring for their emotional and spiritual well-being is more challenging than with laypeople. Monks who have counselled their own family, friends and laypeople throughout their lives in particular, tend to rehearse their own teachings to the hospital staff, saying that they aren’t afraid of death or that there is nothing to fear, when in fact, their behavior reveals the opposite. They isolate themselves, lose interest in other people and turn their faces away when approached by the nurses, which may give the inexperienced onlooker the wrong impression. Experienced nurses who can listen and coax out the true needs of these monks are therefore vital to providing them with the proper care.

In terms of social well-being, some monks had already isolated themselves from others at the temple; when they fell ill, other monks at the temple were hesitant to approach them. They find themselves alone and bedridden, watching only the ceiling. Hospital staff have to cultivate a relationship with them: sitting by their bed or remaining nearby every day, whether or not their patient chooses to speak to them or not, to wait for him to open up in his own time. However, this kind of care has its limitations, as most of the staff already have their hands full, and must truly see the value of providing this kind of attention, to carve time out to be with them.

When it comes to social and spiritual well-being, it is apparent that having volunteer monks, who understand the spiritual and relational needs of the patient, come in and provide regular bedside companionship can greatly alleviate the nurses’ responsibilities, especially in matters that nurses struggle or are unable to address such as the deathbed confession, which can only be facilitated by a fellow monk. A volunteer group of monks called Gilanadhamma, for example, travel to many hospitals to provide spiritual counsel to terminally-ill laypeople.

Though various public and private healthcare institutions such as the Department of Health, the Thai Health Foundation and Maha Chulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya University have jointly created Phra Kilanupathak (public health volunteer monks of each temple) to invest in the health and well-being of monks across the country, the initiative is still in its early stages and has not had a clear impact on end-of-life care for monks.

At present, most hospitals might have a good understanding of palliative care; however, the palliative care system is riddled with no small amount of problems and still not accessible to all. Hospices for terminally-ill monks, in addition to hospitals that prioritize fully supporting their patients’ spiritual growth over physically treating the disease, can provide another interesting alternative.

Caring for one another is the way forward

After listening to experts, learning more about palliative care and a buddhist approach to end-of-life care, drafting their living wills and reflecting what they had collectively learned in the seminar, the gathered monks were all in agreement that looking after and being able to rely on one another is of critical importance. Towards the end of the seminar, the conversation moved towards contributions each participant wanted to make towards support systems for monks, challenges that they had encountered when caring for patients and what kind of help and support they would need from each other moving forward.

Many of the gathered monks began with discussing their own self-development, whether that was to bring down certain internalized aversions regarding notions of comfort, either from looking after bedridden monks at the temple and being unable to bear the smell of their urine and feces or becoming bored dealing with certain patients. Some become irritated by patients with deteriorating mental faculties who repeat the same stories over and over again, but as death draws near, they find that their former irritation dissolves into sympathy for the patient and remorse that they shouldn’t get frustrated so easily. Many are inspired to broach the subject of living wills with their family and fellow monks at the temple, and to slowly begin educating themselves on end-of-life care and visiting sick monks at their own temple.

Some of the laypeople at the seminar gained insight into opportunities to approach the abbot of certain temples that have a demonstrated interest in and facilities for palliative care but are lacking in staff, with the intention of filling in that gap.

Though what was shared at the seminar, especially the discussion of current obstacles and ways of circumventing them, may not be fully realized solutions, they were still valuable because they came from lived experience and can be implemented in real life.

Everyone agreed that mutual care among monks is the key. It can start small, with the monks around them, and slowly grow. Undergirding this framework is that caring for sick monks is to embody buddhist philosophy: volunteers aren’t simply giving but also enlightened by the monks’ sicknesses. With a change in mindset from seeing patients as teachers rather than burdens, caregiving will become an opportunity for spiritual growth.

Citations:

- “Attending sick monks and spiritual development” seimar 4-6 feb 2019 at Wat Siripong Thamnimit, Bangkok.

- “Santibhavan”: The Story Behind Thailand’s First Hospice for Monks” https://peacefuldeath.co/santiphawan/

- In addition to Santibhavan, there are also other monks’ hospices in Thailand such as the Pamakham Home for Monks at Pakchong, Nakorn Ratchasima. Although it isn’t a hospice that focuses on emotional and spiritual well-being, it does offer treatment and a place for monks to stay until they recover or pass away. Phra Vichit Thammachito visited them to learn about their organisation and was generously given resources and equipment for Santiphawan.

Important people mentioned: Pornsap Tesakulcharoen, Phra Paisal Visalo, Phra Vichit Thammachito