Story: Punyaapa Srikirin

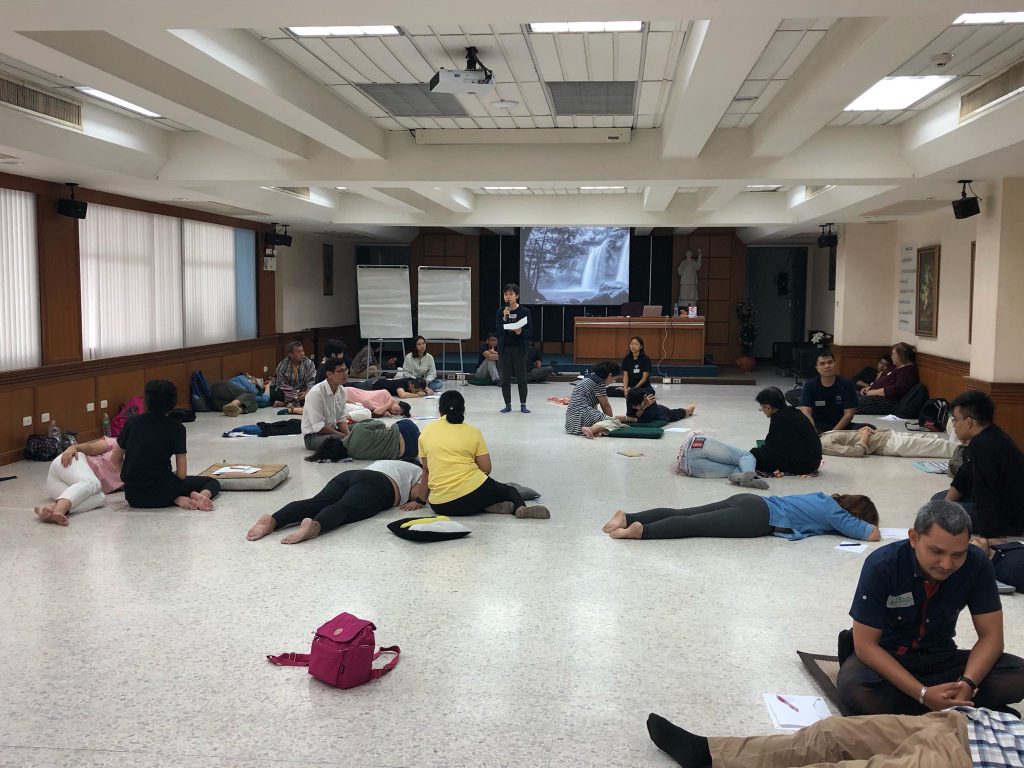

In August last year, Peaceful Death selected fifty community leaders from across the country to attend the “Workshop for Community Facilitators: Communicating Compassionately and Creatively with Others”.

Filled with a gamut of fun and insightful activities, the two day workshop was designed with the aim of equipping participants with various tools and concepts that they can then adapt and integrate into their palliative care and peaceful death- related work in their respective communities. The group of participants represented a range of occupations and ages. We interviewed a few, all of whom have fascinating perspectives on the content of the workshop and ideas for incorporating what they’ve learned into their practices.

Senior Sergeant Major Chaikarn Watthakam

“My name is Seua, and I’m a policeman”

The stern, well-built man standing before me introduces himself in a curt but gentle manner before sharing his story.

In addition to serving in the police force, Senior Sergeant Major Chaikarn Wawtthakam, or “Phi Seua”, also mentors incarcerated people. Over his 26 years of service, Phi Seua has interacted with countless offenders inside and outside the system. The nature of his work demands not only vigilant care of his physical and emotional health, but something else that is an indispensable skill and sensibility: the art of listening.

“Sometimes a prisoner will respond in a certain way, but there is a deeper, hidden meaning beneath their words. It’s like an iceberg, we have to look for the truth beneath the surface of what they are saying.”

Phi Seua explains that the non violent communication (NVC) workshop teaches compassionate listening; that is, a way of perceiving the feelings and needs of the person you are talking to without judgement. Often, we inadvertently judge what someone is saying or their actions, without truly understanding their deeper needs.

In addition to listening, “touch” is also an important skill in police work. The “Touch Skills Training” workshop was therefore of particular interest for Phi Seua, who explains that touch is the foundation of the behavioral sciences. He frequently finds that dialogue and listening prove inadequate when communicating with incarcerated individuals. In such situations, touch is a pivotal skill. Observing body language and providing touch at the right moment is a crucial aspect of police work that requires a lot of skill and sensitivity. Admittedly, touch can indicate untoward intentions, but in other contexts, touch can provide encouragement and strength that has nothing to do with excavating some deeper meaning at all. In his role as a mentor to incarcerated people, for example, he is more interested in providing encouragement and alternative pathways, and drawing out each individual’s potential, to help them stay out of trouble and build stable lives when they leave.

“I was a rebellious kid, with marks and scars all over my body, but I was able to pull myself out of it. However rebellious I was, I dedicated myself to studying just as hard. We all have the ability to control the compass arrow of our lives. I believe that they (the men in prison) can do it too. I talk to them, touch them, to show them that are not loathed and encourage them. Touch and encouragement can help these men feel valued and confident enough to set new goals for themselves. After all, touch isn’t just holding hands; it’s about touching people’s hearts and sharing our passion for life with one another,” Senior Sergeant Major Chaikarn Wawtthakam says in parting.

Dr. Chanokporn Puapattanakun

If we cast our minds back to our Thai lessons ten years ago, those hours of spelling, sentence construction, reading comprehension and recitations of poetry and prose in front of the classroom that lulled everyone to sleep, are probably what come to mind for many of us. But nowadays, Thai classes are a long way ahead of what they used to be.

Dr. Chanokporn Puapattanakun, a lecturer in the Department of Thai Language at the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Mahidol University, says that thai studies within the context of the university, is much changed from the past. In the thai language program, the students’ language studies is supplemented by classes in “communicating and listening”, in which ‘communicating’ is no longer about speaking in front of the class with ease and authority nor is ‘listening’ merely a matter of language comprehension.

Dr. Chaonporn takes us back to the catalyst of this recent turn, explaining that over the past ten years, the university has deliberately invested in listening skills training. Such ideas weren’t widespread in the past, but over the last decade, certain groups, such as doctors and nurses, who were familiar with these concepts, began entering the university and taking up positions in various departments. This propelled an increased interest in communication and listening skills within those departments. Mahidol University even has a Contemplative Education Centre dedicated to teaching attentive listening methods such as NVC, which have been consistently incorporated into Mahidol’s pedagogy through the years. Dr. Chanoporn, who is also a medical professor, also wants to play a part in further weaving these practices into medical pedagogy.

In his class, “The Art of Using Thai in Communication”, one of the requisite courses for first year students in all departments at Mahidol, Dr. Chanoporn tries to insert sections on attentive listening. He believes that listening skills can be a valuable asset in medical education in particular, since medical students will have to interface with many different kinds of people despite being relatively young and inexperienced. Additionally, students are expected to not only treat patients, but to have difficult conversations with patients and their families. Skillful communication is therefore vital to finding ways to bring all parties in a discussion to a common understanding in a peaceable manner.

“I’m used to people dying but patients don’t deal with death in their daily lives. Facing their own death is their first and significant encounter with it. One person experiences it as ordinary, the other as a profound existential crisis. So, what can we do so that these two parties attune to one another better?”

The compassionate listening or NVC skills session introduced important tools for understanding and attending to the needs of one’s interlocutor in conversation that Dr. Chanoporn will tweak and incorporate into his curriculum for doctors and nurses in training. For example, he may ask his students to think of something a patient has said that hurt them, then ask them to reflect on why a patient may have responded to a medical professional in that manner and pay attention to what may have gone unspoken.

“Before, we only looked to hard and fast formulas that told us how to respond if a patient says or behaves a certain way. Nowadays, we should attend to the inner needs and feelings of patients as well.”

A new pedagogical exercise that has recently been introduced to the curriculum, in which students role play as patients and their families, and interact with one another in their roles as medical professionals, patients and relatives. Then, they reflect on the needs and emotional state of each of the characters, which, at the very least, improves their ability to empathize with all parties involved.

“I hope that when we go to the hospital in 5-6 years, we will meet doctors who are emotionally attuned to their patients, and appear more human than they do now,” Dr. Chanoporn concludes with a laugh.

Doctor Suthi Rattanamongkonkul

Schools aren’t just spaces reserved for the education of young people, as the “Schools for the Elderly” foundation, established by Srinakharinwirot University’s Faculty of Medicine, demonstrates. One of its faculty members, Dr. Suthi Rattanamongkonkul, was a participant in our workshop. The foundation’s purpose, Dr. Rattanamongkonkul says, is to motivate elderly people to enroll and learn about certain important facets of aging, such as bodily changes, pertinent public policies, and age-appropriate exercises for staying healthy. Most importantly, they come to an understanding of the reality of life as elderly people, and the necessities that come with it, such as making preparations for their death. They may reflect on how they want to die, any lingering concerns or regrets they may have, as well as how they want their funeral to be arranged and the financial preparations that need to be made. Participating in Peaceful Death’s workshop has provided Dr. Suthi with many tools that complement his work. The “Card Game for Decoding Life”, for example, can provide his elderly students with greater clarity on their needs, and help them prepare and make arrangements for their own death. In his experience, candidly talking about death with the elderly students is often difficult:

“All the questions on the cards are very approachable and get people talking to one another. With the card game leading us, the conversation proceeds smoothly, and we don’t feel too awkward to ask each other questions like before.” says Dr. Suthi.