Story: Pongkamon Surat

On the May 29th, 2019, the Arsom Silp Institute for the Arts, Thai Health Promotion and partner organisations held an installment of the “You and I, (Being) Happy Together,” seminar series titled “Yuen Thin Lang Ong Phra” (“Visiting the Place Behind the Buddha Image”). Hosted in the communal area of the Baan Uea Arthorn Neighborhood (on Phutthamonthon Sai 5 Road, Amphoe Sam Phran, Nakhon Pathom), the seminar brought together four model communities of collective well-being and invited members from these communities to meet

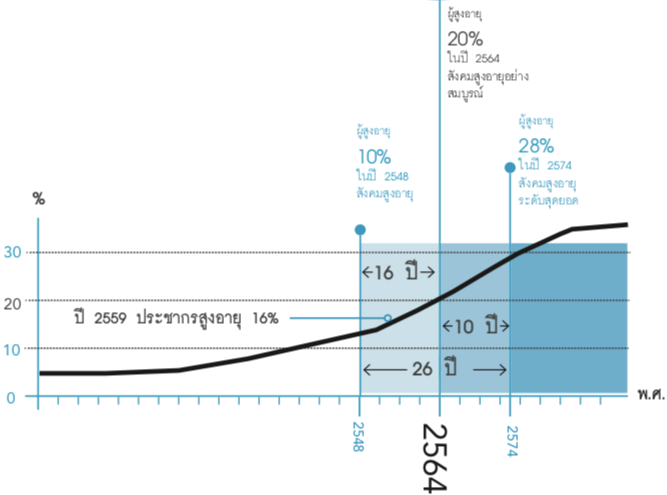

In 2015, the World Health Organization announced a “Healthy Ageing” framework oriented towards helping seniors live the entirety of their lives in a meaningful way with respect to their intrinsic capacity (emotional and physical capabilities). The global community is in the process of preparing for the advent of ageing societies, as a growing senior population will reconfigure various facets of society, such as the economy, politics and healthcare. Experts predict that Thailand will become an aged society, where there will be more than 20 seniors per 100 of the total population, in 2021.

Many countries have introduced specific healthcare legislation for senior citizens in different age brackets that emphasizes holistic coverage, accessibility and quality of care. As the world’s senior population grows, countries will have to devise long-term strategies to respond to lengthening life expectancies, as well as the growing prevalence of chronic diseases. Most terminally or chronically-ill seniors are looked after by healthcare professionals or family and either stay at hospitals, live at home or move into private assisted living communities. However, a number of seniors who are placed into assisted living facilities do not have access to proper end of life care, and pass away in isolation from their family and friends.

[A graph of the growth of Thailand’s senior population by year. By 2021, Thailand will be an aged society, and within another ten years, will be a super-aged society. From: thaitgri.org/?p=38427]

In Thailand, Social Welfare Development Centres for Older Persons, or old people’s homes, as they are more commonly known, occupies only a small tract of the social landscape, and yet constitutes in themselves an entire world — often, for many seniors, their final world. There are twelve of these centres across the country. Some of the seniors are without family, or family that will take care of them, others are there because they don’t want to burden their loved ones, or want to be in a community of peers. Some are visited by family members, others rarely. Therefore, the bulk of the responsibility for senior residents’ healthcare falls on the staff, and when necessary, affiliated hospitals.

This article will introduce you to the circumstances of these residents, and in particular, those who are terminally and chronically-ill. Most of them are bedridden and require special care, and are often forgotten about in Thai society. The Bang Khae Old People’s Home, in Phasi Charoen, will be our case study.

The Terminally and Chronically-Ill Residents of the Bang Khae Old People’s Home

The Bang Khae Social Welfare Development Centre for Older Persons was first called the Bang Khae Welfare Home for the Elderly when it was founded during the Phibun regime as the first old people’s home in Thailand. According to their physical health and capabilities, residents live in one of three living facilities, which are (1) the facility for seniors capable of taking care of themselves, (2) the facility for seniors capable of taking care of themselves with special equipment, and (3) the facility for bedridden or chronically-ill patients in the nursing home with little to no ability to take care of themselves.

The first two groups do not share the medical issues of the third group, who need special care. Some of the residents who fall under the third category were diagnosed with cancer while at the home, others are terminally-ill seniors, without family and viable treatment options, or in some cases, with family that send them to spend the rest of their lives at the home in lieu of caring for them. The primary caregivers in each facility are the nurses, whose responsibilities include feeding medicine, administering blended food through a feeding tube, giving bed baths, changing diapers and caring for the residents’ overall health and well-being until they take their last breath. However, if a resident is in a critical condition that exceeds the home’s medical capacity, they are sent to an affiliated hospital for treatment.

[The Bang Khae Social Welfare Development Centre for Older Persons. From: banbangkhae.go.th]

The Blindspots in Nursing Home Care for Terminally and Chronically-ill Residents

Below are the main problems and obstacles in caring for chronically-ill patients in old people’s homes, based on interviews with officials from the Department of Older Persons (DOP) who have many years of experience in caring for elderly home residents, and staff from the Bang Khae Old People’s Home.

- An Absence of Dialogue or Planning in Preparation for Death

Lars Tornstam, a Swedish sociologist who developed the theory of gerotranscendence in his research, says that older people are in a stage of life in which they are able to understand and accept the nature of life with equanimity. The phase begins at the outset of adulthood and progresses into old age. Their way of life and cultural influences can vary the process for different people, but the general trend appears to be that older people who are content with their lives will naturally begin to prepare themselves for death. With a deeper appreciation of the nature of life, they are more accepting of death than before, or in other words, less afraid of death.

Through the lens of Tornstam’s theory, many older people seem to be capable of reconciling themselves to death and letting go late in life. Some become more interested in religion and get involved in charitable work. Others, however, still maintain a vice grip on life, unable to let go and fearful of death. This is often the consequence of their life experiences, which includes their immersion in a culture that treats death as ominous. For example, Sirinut Antonsen, the director of the Bang Khae Old People’s Home (her position at the time of the interview), shares that “[The residents] will hardly ever talk about death (she shakes her head). Just to ask them about their will makes them scared, because some of these seniors have given everything they had to their children, only for their children to throw it all away. These stories get passed around and make them all scared. It’s hard to change the belief too, that as soon as they write their will they will be abandoned.”

Although people tend to be better able to reconcile themselves to death in old age, many older people in Thai society still see death as inauspicious, and therefore refuse to talk about it and prepare themselves for death in an appropriate manner. No small number of residents in the home avoid talking about death and settling their affairs. Furthermore, curriculum in schools for the elderly, and professional caregiving training overseen by the Department of Health and the Department of Skill Development, still lack a clear discussion of preparations for death, even though preparing for death is an important matter for older people.

That being said, the Bang Khae Old People’s Home has begun introducing programming on the subject of preparing peacefully for death for their senior community volunteers and students at the school for the elderly. They have organised workshops that invite participants to reflect on their lives and fill out “healing journals” (a living will that states the writer’s preferences for end-of-life treatment or care) in collaboration with Peaceful Death, and emotional healing sessions for caregiving staff with Care Club.

[The director of the Bang Khae Old People’s Home and Peaceful Death meet to plan a workshop on preparing for death for the home’s residents and staff]

ร่วมประชุมแผนงานอบรมการเตรียมตัวตาย ให้กับผู้สูงอายุและเจ้าหน้าที่บ้านบางแค

2. Fatigue and Stress Among Elderly Home Staff

Caring for chronically-ill residents with late-stage cancer, Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s is a challenging job that requires physical and emotional strength. Working in 24 hour shifts, the nurses become tired and stressed by the demands of their work, and as a result, are unable to give residents nearing the end of their life the care they should receive. Although the staff are trained in senior care, they lack experience and knowledge when it comes to end-of-life patients and therefore are only able to alleviate their physical discomfort at the outset of illness. However, caring for these seniors is a delicate task that requires an understanding of all facets of their emotional, social and spiritual well-being, as well as the ability to communicate effectively with them.

- A Lack of Specialised Healthcare Professionals, Funding and Equipment for End-of-Life Care

The purview of old people’s homes in Thailand tends to be limited to providing seniors a place to live and looking after their education, quality of life and welfare benefits. They can provide healthcare treatment for non-critical illnesses, and if not, send residents to the hospital. The staff are generally focused on improving residents’ quality of life, which does not leave much room for end-of-life care or preparing for death. Spiritual activities are limited to making merit, even though to nurture spirituality should, in fact, be an undertaking that encompasses beliefs, hopes, religion, the cultivation of healthy relationships and the things that give meaning to life, the ability to choose one’s path and take care of one’s duties, and in the process, live meaningfully with a positive perspective on life.

In the case of the Bang Khae Old People’s Home, there are very few nurses and a lack of specialised healthcare for end-of-life residents. In emergencies, the residents are sent to the hospital without a prior arrangement of what each individual’s end-of-life care preferences are. Additionally, the home lacks the funding and equipment needed to care for end-of-life residents, which is a policy issue inseparable from the shortcomings of a government that does not consider the well-being of the senior population holistically. With these limitations, the Bang Khae Old People’s Home attempts to maintain and augment the independence of their residents for as long as possible, and help them have the best quality of life possible.

- The Difficulty of Determining the Final Stage of Life

Gauging when an elderly individual has entered the final stage of their life is quite difficult. When an older person is seriously ill, they will pass away in a short while. However, seniors who have had a common illness for a long time, or who become slightly sick, may suddenly pass away as a result of the underlying deterioration of their physical health. There was once a healthy resident at the Bang Khae Old People’s Home who had diarrhea for a day and suddenly passed away.

After tracking a group of 4,709 seniors, researchers in England found that seniors over 80 years old are more likely to experience an unexpected death and additionally, that senior residents in old people’s homes and assisted living facilities are the most likely to suddenly pass away in comparison to their peers that live with relatives, friends or an aide at home. Therefore, preparing for the final stage of life leading up to death, especially for residents in old people’s homes, should begin from early on.

Nonetheless, it is not just care homes in Thailand, but institutions for seniors all over the world that struggle to provide adequate care for terminally-ill residents in their last stage of life, partly because of the trickiness of determining when a patient is near death. These seniors require specialised and multifaceted care that simultaneously tends to many aspects of their well-being and centers them and their needs while they are still responsive, rather than when they are already close to death.

Furthermore, a synthesis of more than 1,305 studies on end-of-life seniors living at nursing homes discovered that many of them had psychosocial issues, and had felt isolated and depressed, which indicates that insufficient attention was given to their spiritual well-being. There has to be continuity among staff working with these seniors, and greater access to resources such as labor, funding and time.

In Hong Kong, there is also a growing awareness of the concerning circumstances of terminally-ill seniors who pass away in senior homes. As is the case in Thailand, the staff at their homes are not equipped with the skills to care for terminally-ill. Over the last decade, however, the Hong Kong government has tried to foster conditions that will provide these seniors with a more peaceful death, such as by encouraging advance care planning and, in 2015, building community networks for end-stage patient support.

- Senior Residents Do Not Have Family to Care for Them at the End of Their Lives.

The presence of family plays an important role in helping older people approach death peacefully and comfortably, in an atmosphere of warmth, with the opportunity to give parting instructions, make amends, and express gratitude and love. In her interview, the director of the Bang Khae Old People’s Home reveals that most of their terminally-ill residents are never visited by family and seldom do family return to bring their elderly relatives back home and care for them. Residents usually approach the end of their lives with nurses and staff that they may not have a close relationship with. The personnel may not know what residents’ needs are or have much training in end-of-life care, and therefore be unable to properly attend to a resident’s social, emotional and spiritual well-being.

A Thai study once conducted in-depth interviews with 18 residents of a particular elderly home on their end-of-life preferences. It found that the majority of the interviewees wanted to meet their family before passing away, and had asked the staff to contact their family. There were others who did not want to be visited by family, because of abiding discord and conflict, or the fear of becoming a burden to their loved ones. Their preferences were to be cared for in both health and spirit by the nurses, as if they were family.

In America, 707 nurse researchers and social workers from 52 nursing homes in Indiana were involved in a study that found that the most common issues among residents were the absence of a caring family, isolation and the disregard of their personhood at the end of their lives. The information from the Bang Khae Old People’s Home and the aforementioned research demonstrates, at the very least, that a significant number of the residents of old people’s homes and assisted living facilities have troubled relationships with their families. However, many of these residents still love and care for their children and younger family members, and want to be visited by them before passing away.

Evidently, the shortcomings in palliative care for seniors with chronic and terminal illnesses are problems in communication, disregard of social well-being, family relationships, financial arrangements for care and access to palliative care, not to mention that the likelihood of suddenly passing away increases with age. As a result, many residents of old people’s homes do not receive proper care and quality of life at the end of their lives. The government should treat old people’s homes as long-term care that must be radically transformed in order for residents to both live well and die well.

In light of this, the author of this article would like to put forward the following suggestions for policy makers involved in welfare allocation for long-term care facilities and old people’s homes:

- A culture of openness and acceptance of death must be fostered in old people’s homes. Residents should have the opportunity to visit sick and bedridden friends, and to participate in a range of social activities. Some of these activities should address the subject of death and dying, and begin with encouraging participants to express their own end-of-life needs and preferences along with their life experiences, before slowly introducing different aspects of palliative care preferences when they are at the end of their lives.

- Greater emphasis should be placed on the role of families in senior care. When seniors that still have visiting family members arrive at the last stage of their life, their families should be told that they can still play an important role in their well-being, even if they can’t bring the resident home. Family members can be encouraged to visit on important occasions, help bathe and feed seniors their medicine, and show them love and care. Alternatively, other people who aren’t family but who mean a lot to the dying resident, such as other residents in the home, staff that they are close to, community volunteers and pets, can be brought in for support and companionship.

- There should be a discussion with each senior about what gives their life meaning upon their arrival at the home, in order to begin planning and collecting information for their living will, which states their preferences for palliative care. This will protect the senior from unwanted procedures in the emergency room.

- All old people’s homes should have a unit that specializes in end-of-life care or at the very least be affiliated with a hospital with a palliative care centre that will admit residents and jointly care for them. There should also be training programs in end-of-life care for staff and nurses at old people’s homes, which should be organized by the government, hospitals and palliative care organisations.

- Staff and nurses that care for end-of-life residents should have access to emotional support services. These services should foster a positive perspective on their work and emphasize their instrumental role in supporting senior residents’ well-being, so that they continue to feel inspired to do their work.

Interviewees: Sirinuch Anthornsen (former director of the Bang Khae Social Welfare Development Centre for Older Persons, current director of The Division for the Promotion of Older Persons); Onuma Inthachai (specialized social worker).

Citations

1. World Health Organization. (2015). World report on aging and Health. Luxemburg: WHO Press.

2. World Health Organization. (2017) Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. January 10, 2019, from https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf

3. มูลนิธิสถาบันวิจัยและพัฒนาผู้สูงอายุไทย (2559). สถานการณ์ผู้สูงอายุไทย พ.ศ. 2559. สืบค้นเมื่อ 5 มีนาคม 2562, จาก http://thaitgri.org/?p=38427

4. United Nations. (2017). Addressing the Challenges of Population Ageing in Asia and the Pacific: Implementation of The Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing Retrieved May 21, 2019, from https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/Addressing%20the %20Challenges%20of%20Population%20Ageing%20in%20Asia%20and%20the%20Pacific.pdf

5. Tornstam, L. (2011). Maturing into Gerotranscendence. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 43(2): 166-180.

6. Hermann, C.P. (2001) Spiritual needs of dying patients: A qualitative study. Oncology Nursing Forum. 28(1): 67-72.

7. Teggi D. (2018). Unexpected death in ill old age: An analysis of disadvantaged dying in the English old population. Social Science & Medicine. 217: 112–120.

8. Greenwood, N; et al. (2018). Experiences of older people dying in nursing homes: a narrative systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 8: 1-13.

9. Luk, J. K. (2017). End-of-life services for older people in residential care homes in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 24(1): 63-67.

10. สิริลักษณ์ โสมานุสรณ์. (2557). ความต้องการการดูแลในระยะสุดท้ายของผู้สูงอายุใน สถานสงเคราะห์คนชรา. วารสารพยาบาลสงขลานครินทร์. (34)1: 71-88.

11. Cagle, J. G; Unroe, K. T; Bunting, M; Bernard, B. L; & Miller, S. C. (2017). Caring for Dying Patients in the Nursing Home: Voices from Frontline Nursing Home Staff. J Pain Symptom Manage. 53(2): 198-207.