Story: Suthisna Lerdsookprasert

Most people think of death as an unfortunate eventuality and are often afraid to talk about it openly. When a close friend or a family member suddenly becomes sick or passes away, we usually feel caught off guard, because we never thought about it or prepared ourselves. Even those who are mindful of the reality of death still find it difficult to touch on the subject.

“The Life Unlock” card game was developed by Peaceful Death to help families or groups of friends to broach the subject of life and death more easily and talk about it in depth. Players reflect on themselves and arrive at a deeper understanding of their loved ones. In times of crisis, they will all be in a position to support one another.

The cards are adapted from a game called “My Gift of Grace” created by Common Practice, an American innovative healthcare company. The company is focused on providing solutions to the general avoidance of discussions on serious illness and death to help healthcare workers, patients and families talk to one another more easily.

The game comes with a deck of many different types of cards, rules for setting up a round and a letter that will help the game leader more smoothly initiate the game and open up discussion. At any rate, Peaceful Death also organises training on leading a “Life Unlock” session, which suggests methods for playing and gives participants direct experience with the game so that they can confidently introduce the game, and open up conversations, with family and friends.

How To Play and The Rules

The way the game begins is with introductions and checking in on how participants are feeling at the moment, to help everyone feel more comfortable with one another. Then follows a listening exercise.

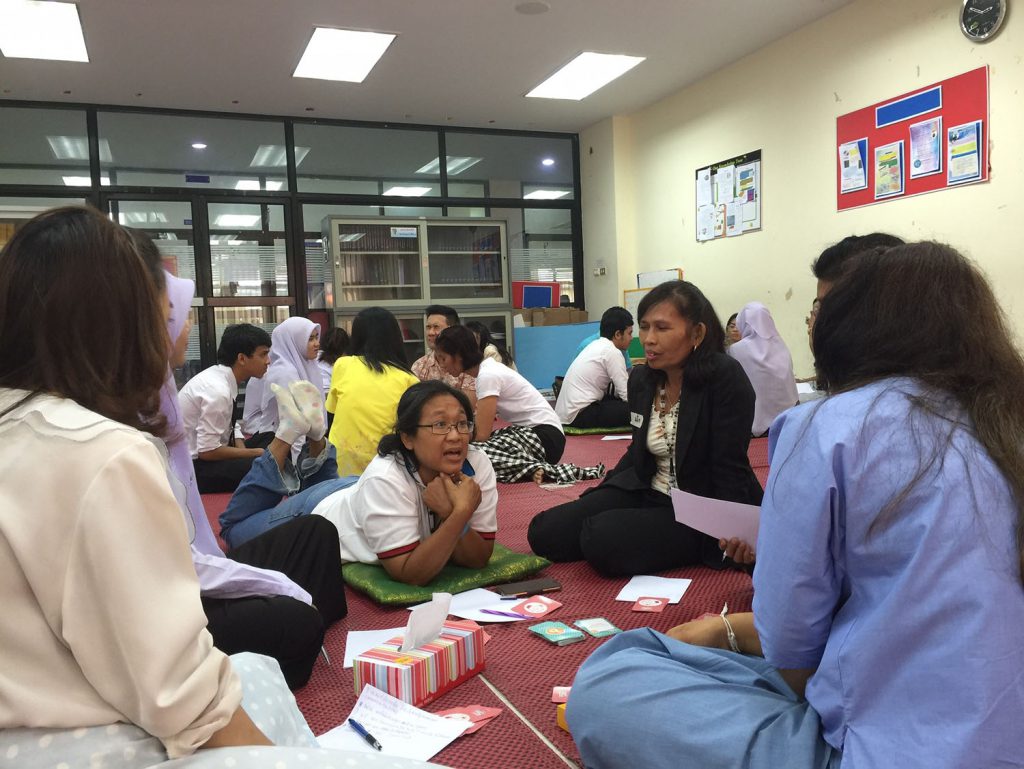

The practice of listening is at the heart of the card game. To begin the exercise, participants pair up and talk to one another based on a series of prompts. At first they talk to each other naturally; usually, most participants won’t be actively listening to their partners at this stage. They may have questions they want to ask, which diminishes their capacity to listen attentively, and sometimes cut off their partner to ask them, or turn their head away. The game leader will point out these behaviors that curtail the ability to actively listen, what their consequences are, and what good listening entails, which is to listen with one’s body and heart. Then, the group practices being good listeners. These exercises help the conversation flow smoothly, fosters deep discussion, and give players the opportunity to truly self-reflect.

Then, the conversation begins with the group responding to a set of phrases in the deck. The leader divides everyone into smaller groups of 4-5 people and gives each participant a piece of paper and a pen for them to write down their responses to each question asked so that during discussion, players aren’t distracted or preoccupied with their own response while someone else is speaking. Then, the leader deals an equal number of “I’m touched” cards to each player, that they can give to any player who shares a response that moves them during conversation. Oftentimes, the “I’m touched” cards imbue the conversation with a lively atmosphere and when players who want to express support for other people in their group, they just can give them the card.

After that, the leader begins asking questions from the “warm up card” with two questions to get players to begin sharing with one another, which are: “Do you have any anxieties or concerns about playing this game” and “What do you hope to receive from this game”? These help ease the tension that players may be feeling.

The most important thing when each player shares their response is that the other players listen attentively, and do not interject with their own thoughts or questions. The leader themselves does not pressure players into answering a question, but ask them to allow the question to guide them to reflect on their own life. Once a player has finished sharing, listeners may ask questions or for further clarification. Then, the players randomly deal out 45 question cards, which investigate how each player thinks about life and death. Questions include: “In this life, how much more money do you need, and why this amount”, “What do you think about that gives you strength and the inspiration to live” and “What do you think is a ‘good death’”?

Players can turn over and answer these questions until the end of the session. Then, the players read the “end of discussion card”, which has two questions: “What are some important things you have learned in this session” and “After the end of this session, what will you change in your life”. Players write their answer to the latter question on a “prayer card”, which they take home with them as a reminder of their resolution.

A “Life Unlock” session lasts 1-2 hours. The leader can read the instructions and the ‘letter to the leader’ from the manual, which also contains suggestions for different situations. For example, if there is an interesting word or phrase that comes up in conversation, the leader may direct the group to reflect on it further for deeper discussion. However, the leader has to be careful not to let their own interests or beliefs encroach on other players.

A piece of advice for leaders is that they should prepare a quiet space, without disturbances or external distractions, that can be divided into separate areas. The temperature of the room should be comfortable, not too hot or cold. These different considerations are crucial to creating a space where players feel safe.

Reflections on Playing The “Life Unlock” Card Game

Art Natsiri Komolphan, one of the people who have participated in a “Life Unlock” session, decided to sign up because he had heard others mention it for a while and wanted to know what the game was like. Furthermore, he had friends who had played the game and then told him that their lives had changed for the better afterwards. So, he became even more intrigued. On top of that, listening to other participants share their experiences had already prompted Art to begin self-reflecting, and he realized that there were many things that he wasn’t prepared to face, and much that he wanted to do. Playing the game inspired Art to focus on nurturing his relationship with his family, as it made him realize that death and loss were much closer to him than he thought.

Od Wanwipa Malainuan, who leads “Key of Life” sessions for healthcare workers, academics, buddhists and the public, observes that death is universal; talking about death is to reflect on life and living. We direct our gaze to how our life in the present will allow us to have a good death. Most people who come to a session are simply curious about the title of the activity — what of life can it solve — and usually aren’t caring for sick family members, as caregivers generally don’t have the time to attend activities such as this. It also seems to be more difficult to talk to patients about death than to raise the subject with family when everyone is in good health, and can engage with mindfulness and clarity — when the unexpected happens, no one is thrown into a state of panic.

After the session, many players reflect that it was easier to talk about death than they expected; the game seemed easy to play, but brought out profound feelings and insights that felt cathartic to share. They saw where they needed to make changes to improve the quality of the time they have left, and the kinds of decisions that ultimately caused them sadness and regret, that they should remind themselves to avoid. As the players shared their responses to one another, there grew a sense of camaraderie in the group, though none of the players had known each other before.

Certain questions in the game, such as “If you could not look after yourself independently, even to go to the bathroom by yourself, who is the first person that comes to mind who you would ask to help you go to the bathroom, and who would you absolutely never ask,” elicited interesting answers from players. Such as a player, who’s answer to both parts of the question was their mother. They explained that their mom is the person they are closest to, but also someone they do not want to burden; therefore, there are reasons for both wanting and not wanting their mother’s help. In Od’s point of view, when we are rejected, we often react with anger or sadness, when in fact, love might be buried in the other’s decision to turn us away. If we can see that love, then we will find happiness in our lives.

Or take the question, “If today is your last day alive, who is the first person you would want to apologize to, and who is the first person you would want to thank, which is one that often makes participants cry when they share their responses. Some are sad because they will never have the chance to say it. One of the players, for example, was sad because they had reprimanded their mom and regretted not apologizing to her before she passed away. As the player began sharing, he started to cry. The other players listening to him felt the intensity of his desire to make amends, as if erupting through a wall, which gave them the courage to share their own stories and feel the profound connection they have as fellow human beings. Od says that talking about death allows players to learn from each other, from the different experiences that give rise to an array of different perspectives. A good death may have a different meaning for each player, but if each person is able to understand what a good death means for them, then they will know what it is they need and how they should prepare themselves. After all, those who can live their life well, will also have a good death too.

Order the “Life Unlock” card game

You can order the “Life Unlock” game at https://peacefuldeath.co/product/เกมไพ่ไขชีวิต/

Or contact the Peaceful Death facebook page, or Line @peacefuldeath

The author would like to thank Wanwipa Malainuan and Natsiri Komolphan for taking the time to be interviewed and sharing their inspirational experiences.

Citation: http://mygiftofgrace.com

Important people mentioned: Wanwipa Malainuan