Story: Patwajee Srisuwan

Photo: The Muang Nam Dam volunteering group and Phatwajee Srisuwan

Thailand has transitioned into an aging society; in a terrain well-prepared to respond to the needs of an aging population, citizens are receiving comprehensive and timely support. One of the provincial organisations that have stood out in this field is the Kalasin municipality, which regularly receives national awards from leading institutions, earning it the nicknames “the Award-Winning Municipality” and “the Municipality of Innovation”.

Over the two days that the author was able to speak to the participants of the Foundation for Happiness at the End of Life, which is a foundation that the Kalasin municipality and the Muang Nam Dam volunteering group founded to raise community awareness of end-of-life planning, as well as establish a program that organizes visits to elderly dependents’ homes. The success of the foundation can not be attributed to good fortune alone; it was realized through the vision of its director and the hard work of municipal staff and village public health volunteers who resolutely committed in their professional and volunteering capacities to transform the Kalasin municipality into a model city, the kind that the dependent and elderly population have only dreamed of.

A Municipality of Pioneers

Many provincial organisations give a lot of importance to supporting their elderly and dependent populations but are kept from realizing their fullest potential by a lack of budget — should they try to tap into budgets for other projects, they risk getting caught during evaluations.

Over the years, the Kalsin municipality has been a provincial organisation that has found a way to marshal a budget from different sources, which have gradually emerged in response to Thailand’s aging population. It is the first provincial organisation to have received funds from the Local Health Security Fund and the Long Term Care Fund for Elderly Dependents, established in 2017, which they distributed as a healthcare stipend to elderly dependents in the area.

Jaruwat Bunperm, the president of the Kalasin municipality, recalls the Kalasin municipality had prepared themselves by certifying their village public health volunteers as elderly care volunteers and then training them in elderly dependent care before the new funding sources were announced. Their team of volunteers were therefore ready to work as trained caregivers.

In addition to this, the municipality had put together a project for surveying the conditions of their housebound/ bedridden/dependent elderly population. Therefore, once a potential source of funding emerged, the municipality was one of the first to apply for and receive a grant. The budget was allocated to their volunteers, such as in providing compensation for elderly care volunteers who had trained in elderly dependent care.

Before we had a budget, our volunteers were already out there, bathing them, washing their hair, cutting their nails and advising dependents and their families on elderly care. They made sure that our elderly patients’ environments didn’t add to their discomfort. Once they began receiving compensation, it only motivated them further.

says Jaruwat.

Moreover, the Kalasin municipality are also pioneers of emergency transportation services for conveying critically-ill patients to and from the hospital, after which the National Health Security Office issued a mandate all municipalities invest part of their Community Health Security Fund in hospital transportation services for their elderly and chronically-ill residents.

In an internationally published report titled “Closing the Health Gaps for the Elderly: Healthcare Justice and Universal Healthcare Coverage in Thailand”, the World Health Organization (WHO) selected the Kalasin municipality as a case study in healthcare justice for the elderly.

On a different note, the Foundation for Happiness at the End of Life, recently founded in 2018, has received staffing and financial support from the Kalasin municipality for training programming for municipal officers, volunteers, citizens and village health volunteers in various communities. Participants are taught the importance of end-of-life planning and volunteer groups for home visits to elderly and sick dependents in the community are created. Undoubtedly, these are concrete and innovative strategies for fostering communities that support elderly dependents, which other communities can adapt and implement in their own spaces.

The results of the initiatives mentioned above have given the Kalasin municipality such a reputation for being pioneers and models in the utilization of Local Health Security Funds that they have been visited by municipalities from across the country who come to study their work. Their success is also corroborated by numerous awards from national organisations: the Phra Pok Klao award for Exceptional Service to State, Private and Public Systems by a Provincial Organisation, which they received three years in a row, leading in to the Phra Pok Klao Gold Award in 2018 and first place in the Grant for Long Term Care Systems for Elderly Dependents from the National Health Security Organisation Branch 7, Khon Kaen. It is also one of twenty municipalities that shortlisted for award for the Municipality with Exceptional Administration in 2019.

At present, the Kalasin municipality is considered as one of the archetypes for community-based elderly care, with 36 communities — a population of 40,000 with 11.2% or 4500 elderly residents — under the wing of the Kalasin Centre for the Improvement of the Quality of Life of the Disabled and Elderly. Kalasin province’s model school for the elderly, the Kalasin School for the Elderly, has a designated building for meetings and fitness activities that is open daily, which also offers classes in body-mind well-being for elderly residents every Thursday.

A Selfless Staff is the Key to Success

A close study of the Muang Nam Dam volunteering group will reveal a tapestry of connections between their volunteers and Kalasin municipality’s officials. It is impossible to say how it came to be: some volunteers had been part of the Muang Nam Dam volunteering group before becoming municipal officials; on the other hand, some began working as municipal officials before joining the volunteering group.

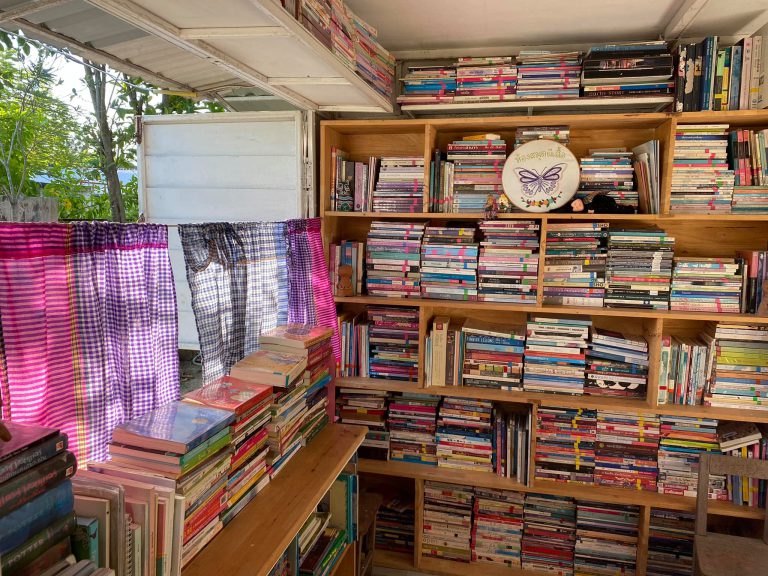

Ja Ae initially formed the volunteering group in order to raise funds for a library in To Rung market around the same time that she began working at the Kalasin municipality. She is currently spearheading the Kalasin municipality’s funding of the Foundation for Happiness at the End of Life.

Cat, one of the first members of the Muang Nam Dam volunteering group, had previously worked for a small provincial administrative organisation. From volunteering to clean the street in front of her house, she moved on to volunteer for the ‘Un Gai Mai Nao Jai’ (Warm Bodies and Hearts) Foundation. She then took on a position at the Kalasin municipality as a social worker for dependents.

Fortunately, our duties in this line of work complement each other. Nowadays, people don’t call the police or the MSDS (Ministry of Social Development and Human Security) when they see an unhoused person wandering the streets — they call me. I contact other organisations in the area and hunt down the appropriate officials. This way they don’t have to wait for their official documents, which takes time. As for the Juthi Sukhawadee foundation, I’m able to help them out because I’m often working in their area. I can tell who is poor and who is trying to appear poor, and who we should and shouldn’t help,

Cat says.

Koi, the Kalasin municipality’s public relations officer, started off as a rescue volunteer for the Metthatham Foundation and still continues to volunteer for the foundation to this day, earning him the nickname “Koi of a Hundred Bodies”. He also volunteers for the Muang Nam Dam volunteering group as well.

As a university student, Ann volunteered in the youth division and democracy division, counselling to children in juvenile detention centres. Once she returned to Kalasin province, she began volunteering with the Metthatham Foundation, the Warm Bodies and Hearts Foundation and the Juthi Sukhawadee foundation. Then, when she became a Kalasin municipal official and began working with Kalasin’s communities, she founded a volunteer initiative that folds sandalwood flowers (used in cremation ceremonies) out of used lottery tickets and donates them to funerals for the poor.

Nok, a physical therapist at the Kalasin municipality’s Center for the Improvement of the Quality of Life of the Disabled and the Elderly, conducts house visits as part of his job. He then joined a home-visiting volunteer group. Pum, the head of the Soi Nam Tip Public Health Centre, also volunteers with the group as a coordinator between bedridden patients in need and home-visiting volunteers. Volunteers such as Pum are all important components and integral to the success of the Muang Nam Dam volunteering group, as they help propel the Kalasin municipality’s public welfare work forwards to the realization of their goals.

All the volunteers mentioned above concur that without the support of the administrative department of the Kalasin municipality, the ability of municipal officers to fully commit to volunteer work would have been severely limited, despite the fact that volunteer groups and municipal public welfare share the same objectives and []

Caregivers Look After Residents… Like Their Own Family

A middle-aged woman describes the condition of “Uncle Putha”, a 74 year old man who has had Alzhemier’s for 8 years and has been bedridden for the last three, as she gently and expertly massages his frail feet as he sleeps. She chats companionably with “Aunt Noi”, his wife, evidence of her familiarity with this patient.

Supicha Buntook, or Pi Noi, was already the president of the village health volunteers and the head of the Wat Ho Trai community in Kalasin before training in caring for sick dependents and becoming a community caregiver.

At first, I started doing house visits when I wanted to, but once the municipality’s foundation was created, I started doing four visits a month, each for two hours. The municipality pays us fifty baht per hour to ask patients about how they’ve been feeling, check their blood pressure, cut their nails, give them massages and give caregiving advice to relatives. Sometimes we rearrange their environment so that they are more comfortable. This patient is bedridden and unable to speak; he doesn’t have any bedsores, his blood pressure is good and his wife looks after him well. I visit my patients often, to give support and encouragement to their family. I’ve been looking after them like this until three of my patients have already peacefully passed away,

Pi Noi reflects.